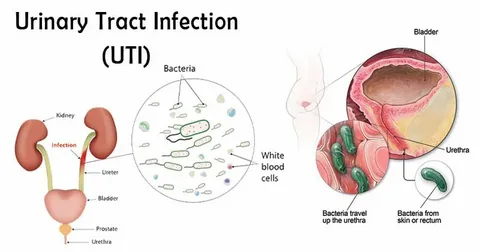

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common bacterial infections in humans, and UTI Dyer represents a concentrated clinical challenge in recurrent and treatment-resistant forms of this condition, particularly among women. What distinguishes UTI Dyer from routine UTIs is its frequent association with persistent infections that do not resolve despite appropriate antibiotic therapy. Emerging research has identified one particularly complex mechanism behind this phenomenon—uropathogen-induced epigenetic remodeling of host urothelial and immune cells. This article delves into how epigenetic reprogramming by bacterial agents contributes to the chronicity and immune evasion in UTI Dyer.

The Epigenetic Dimension of Infection

Epigenetics refers to heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the DNA sequence. These changes are primarily mediated by DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs). In the context of UTI Dyer, uropathogens like Escherichia coli (UPEC), Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis manipulate host epigenetic machinery to downregulate immune responses and promote their own intracellular survival.

This manipulation isn’t merely passive; rather, it represents an evolved bacterial strategy to persist within host tissues, particularly the urothelium, and to establish reservoirs that can seed recurrent infections. Epigenetic changes may silence the expression of toll-like receptors (TLRs), cytokines, and antigen-presentation molecules. In UTI Dyer, this silencing contributes to immune tolerance, allowing pathogens to evade detection and destruction.

Host-Pathogen Crosstalk and Epigenetic Control

One of the hallmarks of UTI Dyeris the dynamic interaction between the host’s immune system and the pathogen’s virulence arsenal. UPEC, the most common causative agent, is known to inject effector proteins via Type III or Type VI secretion systems that can influence host chromatin structure. For example, studies have shown that the UPEC virulence factor CNF1 alters host Rho GTPase signaling, which cascades into chromatin remodeling events that impact immune gene expression.

In bladder epithelial cells from UTI Dyer patients, researchers have found increased levels of histone deacetylases (HDACs), which are known to suppress pro-inflammatory gene transcription. Simultaneously, uropathogens induce histone methylation at H3K27, a repressive marker on genes such as IL-6 and TNF-α. This dual mechanism—repression via HDAC activity and histone methylation—effectively creates a local immune suppression zone, facilitating persistent infection.

Persistent Infections and the Role of DNA Methylation

In recurrent UTI Dyer, DNA methylation patterns differ significantly from those seen in healthy individuals or patients with acute, single-episode UTIs. Pathogen-induced hypermethylation of promoter regions in genes responsible for antigen presentation and neutrophil chemotaxis has been documented. For instance, the CXCL8 gene, critical for neutrophil recruitment, is often found to be epigenetically silenced in bladder epithelial biopsies from UTI Dyer patients.

Moreover, this DNA methylation is not restricted to the site of infection. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from UTI Dyer patients have shown altered methylation signatures that correlate with decreased interferon-gamma production, suggesting systemic immune modulation. Such findings underscore the importance of considering epigenetic biomarkers for both diagnosis and prognosis in UTI Dyer.

Epigenetic Remodeling in Immune Cell Dysfunction

A core feature of UTI Dyer is the failure of immune memory. Typically, innate immune cells like macrophages and dendritic cells retain a form of ‘trained immunity’—a heightened state of alert triggered by previous infections. However, in UTI Dyer, monocytes exhibit a form of tolerance instead, characterized by a blunted response to lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and reduced cytokine production.

This paradoxical immune tolerance is epigenetically enforced. Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation studies reveal that histone marks associated with active gene transcription (H3K4me3, H3K9ac) are absent in key immune response loci in UTI Dyer patients. Instead, repressive marks dominate, impairing the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes even upon repeated pathogen exposure. These findings suggest that the immune system has been epigenetically reprogrammed to ignore infection cues.

Non-coding RNAs and Post-transcriptional Regulation

The impact of non-coding RNAs, particularly miRNAs, is increasingly evident in the pathophysiology of UTI Dyer. Uropathogens induce expression of miRNAs that target mRNAs encoding TLRs, cytokines, and transcription factors. For instance, UPEC infection upregulates miR-146a, a microRNA that suppresses NF-κB signaling. In UTI Dyer, miR-146a levels are significantly elevated in both urothelial cells and urinary exosomes.

These miRNAs serve as potent silencers of inflammation and play a role in establishing a microenvironment conducive to bacterial persistence. In addition, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) such as NEAT1 and MALAT1 have also been implicated in modulating immune responses by altering nuclear architecture and splicing mechanisms. Their upregulation in UTI Dyer signifies a broad epigenetic reprogramming effort driven by the pathogen to establish chronic infection.

Clinical Relevance and Diagnostic Potential

The identification of epigenetic changes specific to UTI Dyer opens new avenues for diagnostics and personalized treatment strategies. Traditional urine cultures often fail to detect intracellular or biofilm-embedded pathogens that are common in UTI Dyer. However, profiling DNA methylation and miRNA expression in urinary epithelial cells or exosomes can offer a non-invasive method for early detection.

Furthermore, the persistence of these epigenetic marks even after bacterial clearance may serve as indicators of relapse risk. Clinical trials are now investigating the use of demethylating agents and HDAC inhibitors in conjunction with antibiotics to reverse epigenetic silencing and re-establish immune responsiveness in UTI Dyer patients.

Therapeutic Implications: Targeting the Epigenome

Given the failure of antibiotics alone to resolve UTI Dyer in many patients, adjunctive therapies targeting the epigenome are gaining traction. For example, the use of vitamin D analogs, known to promote histone acetylation and antimicrobial peptide expression, has shown promise in pilot studies. Similarly, small-molecule inhibitors of HDACs and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are being explored to reverse pathogen-induced silencing.

An important consideration is specificity: broad-spectrum epigenetic drugs may have systemic effects. Therefore, targeted delivery systems—such as liposomal nanocarriers that localize to the bladder—are being developed to modulate epigenetic marks in situ without affecting other tissues. This epigenetic precision medicine approach could transform how UTI Dyer is managed in the future.

The Future: Epigenetics as a Preventive Strategy

Understanding the epigenetic landscape of UTI Dyer not only informs treatment but also holds potential for prevention. Vaccination strategies that consider the epigenetic programming of immune cells could enhance vaccine efficacy by promoting lasting memory. Moreover, pre-treatment screening for epigenetic vulnerabilities—such as hypermethylation of immune genes—could identify at-risk populations, allowing early intervention.

The future of UTI Dyer management may thus lie in the integration of epigenomic profiling with microbiological data, enabling a shift from reactive treatment to proactive, individualized care. This will require multidisciplinary collaboration across urology, genomics, immunology, and systems biology.

FAQs

1. How does epigenetic remodeling contribute to UTI Dyer?

Epigenetic remodeling in UTI Dyer suppresses host immune responses by altering DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA expression. These changes silence key immune genes, allowing uropathogens to persist, evade detection, and trigger recurrent infections.

2. Can epigenetic markers be used to diagnose UTI Dyer?

Yes. Epigenetic markers such as DNA methylation patterns and miRNA profiles can serve as non-invasive diagnostic tools for UTI Dyer, especially in patients with culture-negative but symptomatic recurrent infections.

3. Are there treatments that target epigenetic changes in UTI Dyer?

Emerging therapies include HDAC inhibitors, demethylating agents, and vitamin D analogs. These drugs aim to reverse pathogen-induced epigenetic silencing and restore immune function when combined with antibiotics in UTI Dyer patients.